By Mike Lanchin

BBC World Service

Thirty-six years after surviving one of the worst army massacres in Guatemala’s civil war, Ramiro Osorio Cristales stood up in court last month to give evidence against one of the killers. But the man on trial, a former soldier called Santos López, was not just accused of the murder of Osorio’s family and neighbours, he was also his adoptive father.

“Was I still afraid of him? Yes, I was,” the 41-year-old Osorio says. “But I had to speak out against him. I wanted to be the voice of those who cannot be here.”

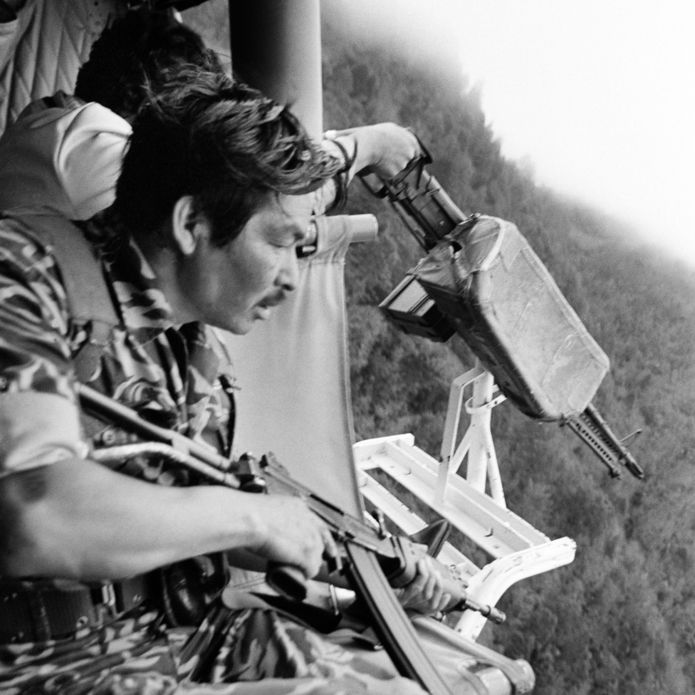

Osorio’s ordeal began in the early hours of 6 December 1982. Then five years old, he was at home asleep with his mother, father and six siblings when López and about 50 other members of Guatemala’s US-trained special operations unit, known as the Kaibiles, entered their village.

The elite anti-guerrilla troops had been sent to the impoverished Mayan settlement in Guatemala’s remote northern jungle after a rebel attack on an army convoy that killed 21 soldiers.

Dressed up as guerrillas in order to divert blame from the army, the Kaibiles went house to house, hammering on each flimsy wooden door, screaming at those inside to open up. When Osorio’s petrified father obeyed, the soldiers grabbed him and tied him up with a rope. They strung the other end of the rope around Osorio’s mother’s neck and marched the whole family to the village square. All the women and younger children were herded into the church, while the men and older children were taken to the school.

Osorio remembers hearing the screaming and shouting as the soldiers interrogated and beat the men. One by one they were shot dead, their bodies piled into the village well.

“When they had finished with the men, they came for the women and children,” Osorio says.

The name of the village, Dos Erres, is now synonymous with the massacre, in which about 200 died.

Find out more

Ramiro Osorio Cristales told his story to Witness on the BBC World Service

Click here for transmission times or to listen online

Overall, more than 200,000 people died during the conflict between the Guatemalan military and Marxist guerrillas. Many were indigenous Mayan civilians, who were accused by the army of sympathising with the rebels. Since war ended in 1996, a small number of officers and lower-ranking soldiers have been prosecuted by Guatemala’s civilian authorities. López was the sixth former Kaibil to be put on trial for the massacre in Dos Erres.

When he gave evidence in court Osorio was allowed a psychologist at his side to help him.

He identified López as one of the soldiers who grabbed his mother and dragged her by her hair from the church. Osorio and his brothers held desperately on to her legs, screaming uncontrollably. She begged them not to hurt her children. One of the soldiers then picked up his baby sister, “dangling her by her legs, like a chicken”. He took her outside and smashed her against a tree “so that she would stop crying”.

Osorio said he didn’t see what happened to his mother or his other brothers. Eventually, exhausted from crying, he fell asleep and when he woke he was alone except for two other small children. When they left the now deserted village, the soldiers took with them Osorio and one of the other infants, a three-year-old named Oscar.

“As we left we passed bodies hanging from trees, people with no limbs, no heads. I recognised one of them as my father,” Osorio says.

The three-day killing spree in Dos Erres was the worst single atrocity committed by the army during the Guatemalan civil war. It came eight months after a group of young army officers, led by a born-again Christian, Gen Efraín Ríos Montt, took power in a coup, promising to crush the rebels and their supporters. During Ríos Montt’s 17-month tenure (he himself was overthrown in a coup in August 1983), an estimated 1,700 indigenous Mayans were killed by the army. He died in April 2018 aged 91 while being tried on charges of genocide.

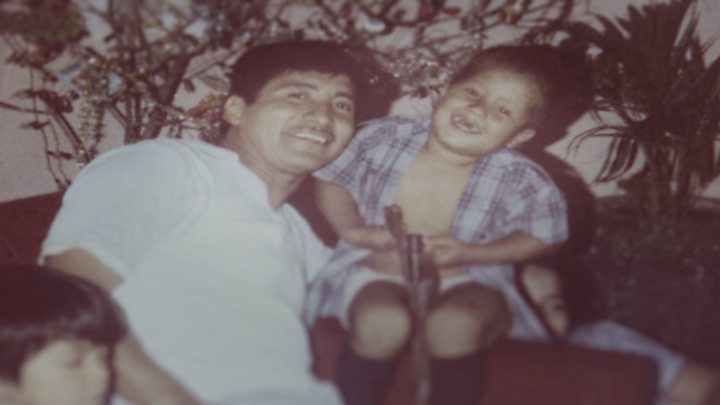

It was while travelling back to the Kaibiles’ base, that López began to take an interest in Osorio, feeding him milk and canned beans from his own rations. Later, the two boys were dressed up in tiny military uniforms, as though they were mascots. López then told Osorio that he had decided to take him home to live with his own family in Retalhuleu, in the south-west of the country.

Osorio says that he was at first delighted by the news, thinking, “I will have a family again.” But his hopes were soon dashed when López put him to work, sent him to school without breakfast and beat him when he complained. “He told me that if I tried to get away, he would find me, wherever I went and kill me.”

Growing up, Osorio says he did not forget his real parents, but never talked about them. He would simply say, when López’s mother-in-law asked him why he cried so much, “I miss my mum.”

He became increasingly desperate to get away from his tormentor, who insisted that he called him “Dad,” but it wasn’t until he was 22 that he made his escape – ironically by joining the army, the very organisation that had murdered his parents, years earlier.

“I was very lost, I didn’t really know who I was,” he says. “It was a very hard choice, but I had to escape, it was such a tough life with them.”

By then it was 1998, the civil war was over and the rebels were forming their own political party. A civilian government was in charge, though the army was still a powerful force. Osorio toyed with the idea of asking someone in the military to help him trace his family, but was too scared. That same year, however, officials from the attorney general’s office and from a human rights organisation came looking for him at the López family house. They were investigating wartime atrocities and had heard that he and Oscar had survived the Dos Erres massacre. Oscar, whose full name was Oscar Ramírez Castañeda, was eventually traced to the US, where he was living. Unlike Osorio, he had grown up happily with the family of another Kaibil and was totally unaware of the fate of his natural family.

Finding Oscar

- The search for Oscar Ramírez Castañeda by a prosecutor investigating the massacre was the subject of a 2017 documentary, Finding Oscar

- It was important to obtain a DNA sample that would match bodies found in Dos Erres and strengthen the case against soldiers accused of the killing

- The prosecutor had the difficult task of explaining to Oscar that he was not who he thought he was – and that his biological father was still alive

Realising suddenly that he could be in danger if his army superiors realised his true identity, Osorio got in touch with the investigators who helped him secure asylum in Canada.

Once there, Osorio thought hard about what had happened. He says that he still felt some gratitude towards López, despite the beatings, the threats and the hardship and even wrote him letters from Canada. But over time, he says, he came to realise that he had been stripped of his roots and his identity. “I had nothing from my past,” he says. “So now I had to build my future.”

In 2016 López was deported from the US, where he had been living illegally, to stand trial in Guatemala.

Osorio struggled with the question of whether to return to testify, but eventually concluded that it was his duty.

Having finished giving evidence, he turned to address the judges with a final plea.

“It is time for justice for all of those who are no longer here, whose light was snuffed out,” he told the packed courtroom. “But one light was left and I am that light. I am asking you to send those who committed this crime into the darkness.”

On 22 November López was sentenced to 5,000 years in jail, 30 years for each of the 171 deaths that he was held responsible for, and another 30 years for the murder of a girl taken away and later killed.

You may also be interested in:

When Vilma Trujillo became mentally ill, the pastor in her village decided to carry out an exorcism to expel her “demons”. She was starved and so badly burned that she died. The BBC’s Vicky Baker visited the remote village to find out how misogyny, belief in the devil and poor education led to murder.

Read: The ‘exorcism’ that ended in murder

Join the conversation – find us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter.